- General Methodology

- Public-Private Partnerships

What Does Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 Measure?

Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 assesses the quality of regulatory frameworks for preparation, procurement, and management of large infrastructure projects. To do this, it relies on standardized questionnaires designed to collect data for further comparison of each country’s regulatory framework with internationally recognized good practices. Identification of internationally recognized good practices for the development of large infrastructure projects through PPP, relied on research of the relevant literature.

Prominent sources that support the preparation of the survey include the World Bank PPP Reference Guide, along with a broader body of literature and related assessments prepared by other international organizations—in particular the IMF Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA) and the OECD Methodology for Assessing Procurement Systems (MAPS). Additionally, the surveys were to a significant extent prepared on the basis of recommendations contained in standards developed by UNCITRAL on public procurement and public-private partnerships. The Model Law on Public Procurement provides procedures and principles aimed at achieving value for money and avoiding abuses in the procurement process, together with e-procurement procedures guidelines fit for the e-government approach. The Legislative Guide on PPPs together with the Model Legislative Provisions are the only existing international legislative models on PPPs. They offer guidance to states and legislators looking to establish a sound legal framework for PPPs. They were adapted in their revised version in 2019 (see Commission Report, para. 71) to incorporate the latest recommendations and good practices from states and experts, especially improvement of project planning and preparation, transparency and PPP-specific contract award procedures.

Thematic Coverage

Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 serves as an indicator of the regulatory quality needed to develop infrastructure projects in those sectors where the intervention of public entities is still necessary to achieve the optimal service level. These sectors vary by country, level of economic development, and cultural and political context.

The Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 survey maintains the questions of the Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2020 as well as the same case study assumptions to support comparability over time.

Geographic Coverage

The Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 PPP survey includes 140 economies, consisting of the 140 economies covered in the Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2020. The geographical distribution of the 140 economies is as follows: 31 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) high-income economies, 19 economies in the Africa Eastern and Southern region, 15 economies in the Africa Western and Central region,17 economies in the East Asia and Pacific (EAP) region, 21 economies in the Europe and Central Asia (ECA) region, 18 economies in the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region, 13 economies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and six economies in the South Asia (SAR) region.

How the Data Were Collected

Survey Contributors

The standardized questionnaires for the PPP were distributed to approximately 13,000 contributors in the 140 economies. Data collection has ended in December 2022. The analysis and validation are still ongoing. Once the initial data collection was completed, a series of follow-ups via conference calls and emails was performed to address and resolve any contradictions or discrepancies in the data provided by various contributors. The preliminary data were finalized and then shared with the World Bank Group’s Country Management Units (CMUs) for comments and validation with each economy’s respective government.

The standardized questionnaires were distributed to practitioners who have knowledge and expertise related to PPPs. Respondents were selected based on their experience and availability to contribute meaningfully to each questionnaire. The report’s main contributors were law firms that have experience advising clients on PPP, public officials involved in establishing and implementing PPP, chambers of commerce, consultants and academics knowledgeable in the topics of PPPs, and others.

The following sources were utilized to identify the appropriate pool of contributors:

International guides, such as Chambers and Partners guides, the International Financial Law Review (IFLR), The Legal 500, Martindale-Hubbell, HG Lawyers’ Global Directory, Who’s Who Legal directory, Lexadin, and country-specific legal directories. The guides permitted the identification of the leading providers of legal services, including their specializations, in each economy;

Major international law, accounting, and consulting firms that have large and well-connected global networks through their partner groups or foreign offices;

Members of the American Bar Association, country bar associations, chambers of commerce, and other legal membership organizations;

Government organizations that formulate PPP in each economy and undertake individual projects, including ministries of finance, ministries of transport, PPP procuring authorities, and PPP units; and

Secondary resources and professional service providers recommended by World Bank staff as well as those found through embassy websites and business chambers.

Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 has updated and extended the database of contributors used in the previous edition.

Scoring and Methodological Changes

The scoring methodology for the Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 data is the same as the one adopted for the previous edition. As in the previous edition, scores for the survey are aggregated for each thematic area: preparation, procurement, contract management, and USPs. Only areas recognized as international good practices were scored. The current scoring methodology allocates the same weight to all benchmarks.

The possible scores range from 0 to 100. Economies with the highest scores, nearing 100, are considered to have PPP frameworks that are closely aligned with international good practices in each thematic area. On the contrary, economies with scores at the bottom (nearing 0) have considerable room for improvement.

The survey is comprised of the same questions as in Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2020. There are no methodological changes. However, for this edition the survey is divided in two parts: a short survey comprised of four questions which aims, primarily, at identifying reforms affecting the PPP legal and regulatory frameworks and a long survey with questions on the thematic area assessed, namely preparation, procurement, contract management and unsolicited proposals in addition to contextual questions on the regulatory and institutional arrangements with respect to PPPs. This has only affected the number of each question included in the survey. This two-phase process allows identifying from the start a pool of economies which have undergone some type of reforms resulting in an initial classification of countries (countries without reforms, countries with reforms (major, minor).

Scope and Limitations of the Assessment

Understanding the scope of the data collected is important to interpreting the results. The data has both strong and weak sides that readers should bear in mind.

Firstly, procurement of both PPPs can be carried out at different levels of government and sometimes along sectoral lines. While the report recognizes associated complexities, because of the limited resources it examines only procuring authorities at either the national or federal level. However, certain exceptions were made for some economies due to their specific constitutional and/or administrative configuration. Australia is represented by the regulatory framework of the State of New South Wales. Additionally, the assessment of Bosnia and Herzegovina is based on the Sarajevo Canton; of the United Arab Emirates, on the Emirate of Dubai; and of the United States, on the Commonwealth of Virginia. This approach was adopted to address the fact that the federal governments in these economies have limited authority regarding PPPs in infrastructure. This limitation, along with their particular constitutional arrangements, makes it unfeasible to evaluate the development of PPPs at the national or federal level.

Secondly, the regulatory framework to procure PPPs may differ across sectors. However, it is not feasible to design a survey that covers different regulations for all possible sectors and types of PPP projects. While most of the answers to both surveys may apply to many or all sectors, contributors were referred to a specific case study for the transportation sector (a highway project) to ensure cross-sectoral and cross-country comparability.

Thirdly, Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 follows the World Bank definition of PPPsi and applies this definition irrespective of the specific terminology used in a country or jurisdiction. It includes such modalities as concessions, build (rehabilitate)-own-operate, build (rehabilitate)-own-transfer, build (rehabilitate)-own-operate-transfer, and similar contract modalities under which an infrastructure asset is built (expanded, reconstructed, or upgraded), owned, and operated by a private partner, and transferred or leased back to a public partner upon expiration of a contract term. In the following economies the authors detected two clearly separate regulatory regimes for concessions (sometimes defined as user-pay arrangements) and PPPs (sometimes defined as government-pays arrangements): Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, France, Mauritius, Niger, the Russian Federation, Senegal, and Togo. For these economies, the concession regime was evaluated and scored separately, but the findings in this report refer exclusively to the PPP regime for consistency.

Fourthly, the Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 survey uses a broad definition for the regulatory framework and includes any applicable legal texts and other binding documents (such as policies, standardized transaction documents, and contracts), as well as judicial decisions and administrative precedents regarding procurement of large infrastructure projects.ii This broad understanding of the regulatory framework helps prevent, to the extent possible, any bias towards a particular legal system (civil law countries versus common law countries) or formal configuration of the regulatory framework.

It is also important to note that Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 does not assess individual PPP projects and contracts on a regular basis or treat them as a source of information. The actual laws and regulations in place as of the cut-off date are used as the main information source.

Moreover, Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 survey questions do not cover all regulatory challenges related to PPP project cycle. In particular, they do not consider the capacity of implementing agencies as demonstrated by staffing numbers, staff competence levels, professionalism, and experience, and macroeconomic stability or the prevalence of corruption in each economy. Additionally, Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 does not capture all the related elements and cannot be considered a complete and full assessment for a straightforward classification of economies based on their capacity to manage the PPP process.

Furthermore, the relevant legal and regulatory provisions noted in the report reflect a moment in time. Thus, readers should note that the legal situations may have changed since then. Specifically, the cut-off date for the Benchmarking Infrastructure Development 2023 report is June 1st, 2022. Hence, any regulatory reforms that occurred after that date are not taken into consideration in this edition of the report.

Finally, the report and the data points are meant to be actionable by lawmakers and governments. Thus, the report highlights the relevant regulatory aspects of the PPP legal frameworks in the hope of giving the governments and parliaments of the respective economies an opportunity to have a critical look at possible areas for improvement within their PPP procurement frameworks and help them in formulating the direction of change that might be needed going forward. However, given the limitations discussed, the report is not meant to be prescriptive and does not attempt to rank economies by their capability to procure PPP projects.

Public-Private Partnerships Methodology

- A private partner (a project company) is a special purpose vehicle (SPV) established by a consortium of the privately-owned firms that operate in a surveyed economy.

- A procuring authority is a national/federal authority in a surveyed economy that is planning to procure the design, build, finance, operation and maintenance of, for example, a [national/federal] infrastructure project in the transportation sector (i.e., a highway) with an estimated investment value of US$150 million (or an equivalent in the local currency) funded with availability payments and/or by user fees.

- For this purpose, a procuring authority initiates a public call for tenders, following a competitive PPP procurement procedure.

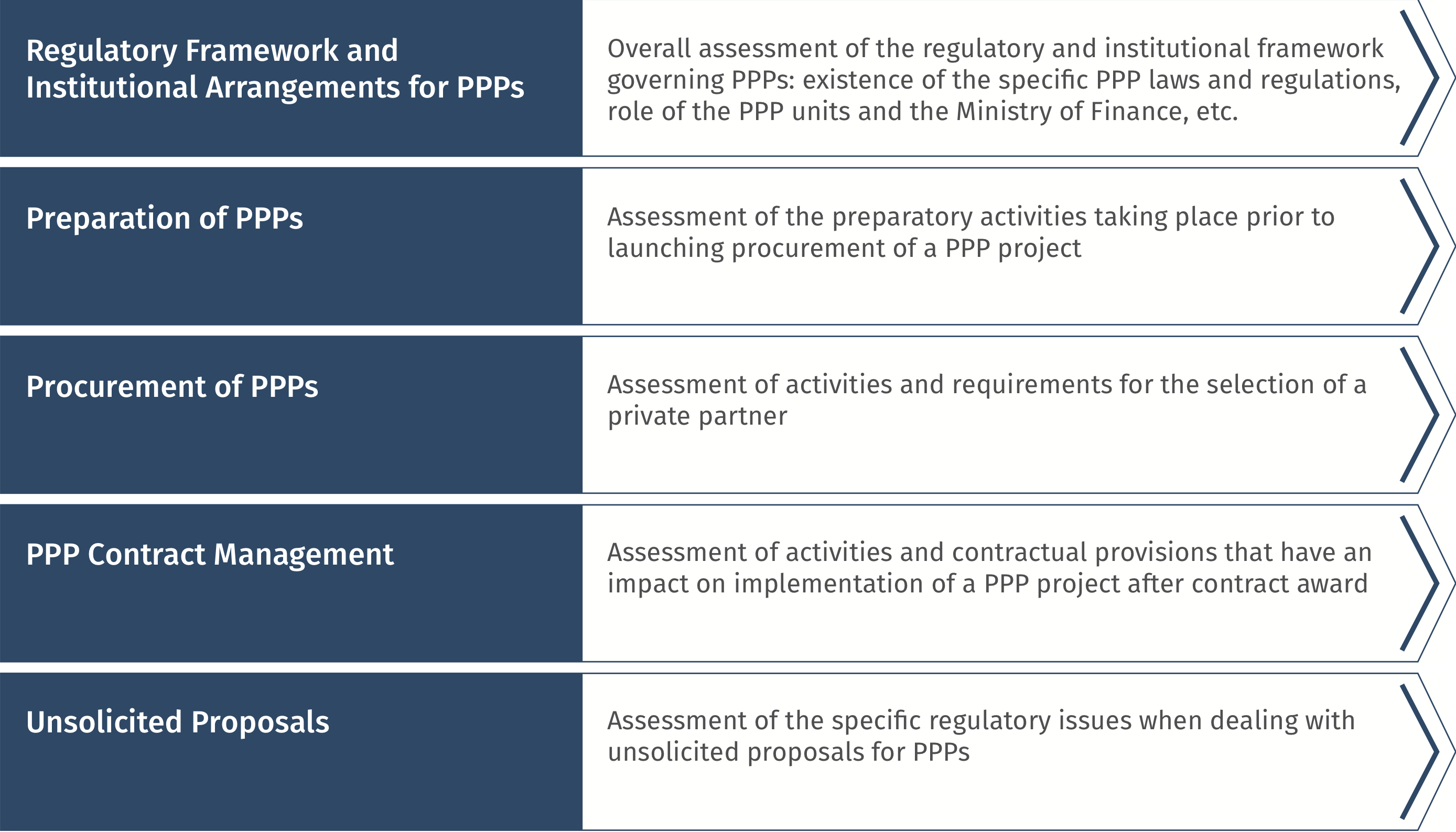

The survey measures key characteristics of a regulatory framework applicable to PPPs at different stages of a project cycle, including its preparation, procurement, and contract management with a special module on unsolicited proposals. Background information on regulatory framework and institutional arrangements is also analyzed for contextual purposes. Figure 1 below describes the focus areas of the survey assessment

PPP Survey Thematic Areas